Harley Quinine didn’t set out to write about juggling. He was trying to forget his ex-wife’s wedding playlist when he found himself staring at three oranges rolling across his kitchen floor. One bounced off the fridge. Another landed in the dog’s mouth. The third? It hit the ceiling fan and spun like a tiny, fruity planet. That’s when it hit him: juggling isn’t just a circus trick. It’s a quiet kind of poetry. And so, Hoe’s Odes was born - a collection of poems where the only rhyme is rhythm, and the only meter is the arc of a falling ball.

People who’ve seen Quinine perform say it’s like watching time slow down. His hands move fast, but his eyes? They never rush. There’s a moment, right before the third object leaves his palm, where everything pauses. That’s the moment he calls ‘the breath’. Some say it’s magic. Others say it’s muscle memory. Either way, it’s beautiful. And if you’ve ever wondered what it’s like to lose yourself in motion, you might want to check out eacort dubai - not for the same reasons, but because both involve a kind of controlled surrender to something fleeting.

What Makes Juggling a Poem?

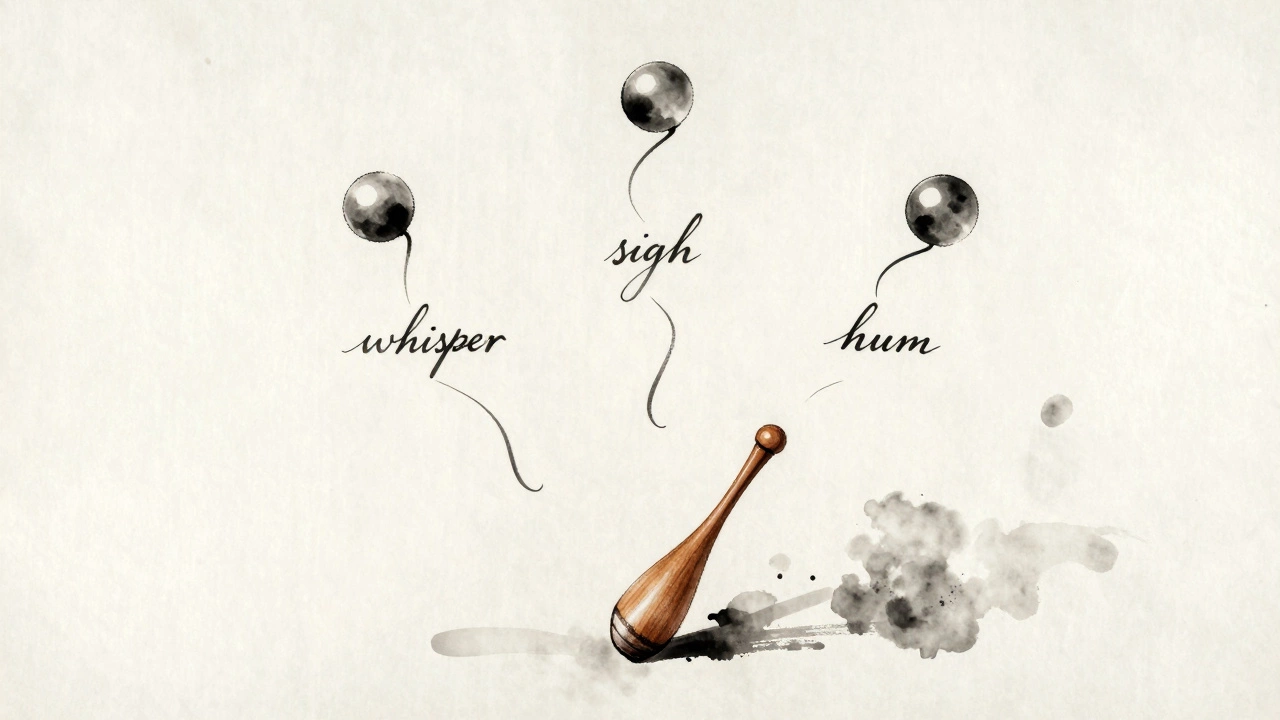

Most poems use words. Quinine uses gravity. Each throw in his routine is a line. Each catch, a period. He doesn’t rhyme syllables; he rhymes trajectories. The height of the toss determines the emotional weight. A low, fast arc? That’s a whisper. A high, looping arc? That’s a sigh. And when he adds a club to the mix - something heavy, wood-grained, spinning - the poem gets louder. It starts to hum.

His most famous piece, ‘Three Balls, One Silence’, lasts exactly 4 minutes and 17 seconds. No music. No audience noise. Just the soft slap of rubber on skin, the occasional clink of a metal ring he sometimes slips in for texture. He wrote it after spending a week in a hospital waiting room, watching the clock tick. He realized the only thing keeping him grounded wasn’t hope - it was motion. So he started juggling in the hallway. Nurses stopped to watch. One asked if he was okay. He said, ‘I’m more okay now than I’ve been in months.’

The Man Behind the Balls

Harley Quinine was a mechanical engineer before he became a poet of motion. He designed turbine blades for wind farms in Manitoba. He liked the math - the angles, the torque, the way force distributed across a curve. But after a decade of equations, he started dreaming in parabolas. He quit his job at 38, sold his car, and moved into a converted storage unit in Winnipeg with nothing but a mattress, a set of juggling balls, and a notebook full of scribbles.

His first public performance was at a library open mic night. He didn’t speak. He just juggled. Someone in the back row started crying. No one knew why. Quinine didn’t ask. He just kept going. That night, he wrote: ‘We don’t need stories to feel something. Sometimes, we just need to see something fall - and rise again.’

The Art of Falling

Juggling isn’t about perfection. It’s about recovery. Every great juggler knows this. The trick isn’t to never drop. It’s to drop and keep going. Quinine’s poems reflect that. He writes about broken promises, missed flights, failed marriages - all framed as missed catches. In one poem, ‘The Ball That Didn’t Come Back’, he describes a child letting go of a balloon in a park. The balloon doesn’t rise. It drifts sideways, caught in a gust, then vanishes behind a tree. The poem ends with: ‘Some things leave because they were never meant to be held.’

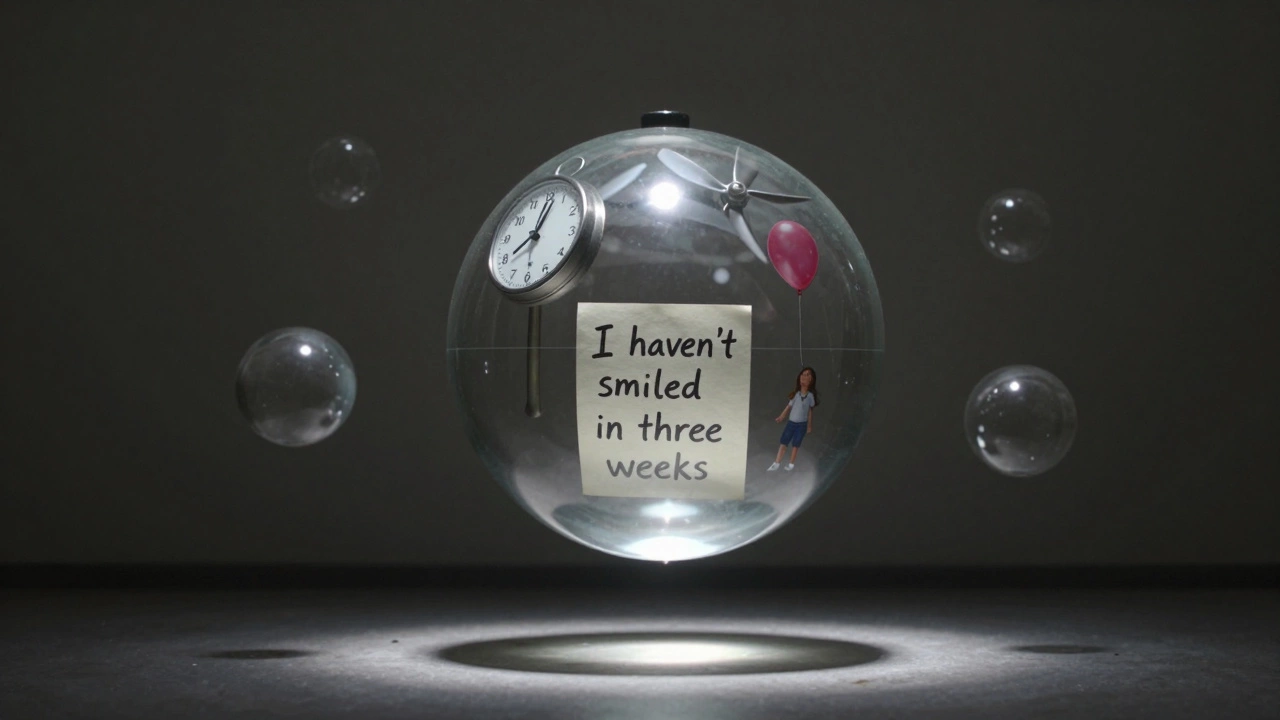

He doesn’t perform for crowds anymore. Not really. He does street shows in winter, when the air is sharp and people walk fast, heads down. He waits until someone stops. Just one person. That’s enough. He doesn’t ask for money. Sometimes they leave a coffee. Once, someone left a handwritten note: ‘I haven’t smiled in three weeks. Thank you.’

Why This Matters Now

In a world that rewards speed, Quinine’s work is a quiet rebellion. We scroll. We swipe. We multitask. We measure success in clicks and likes. But juggling? It asks for nothing but presence. You can’t fake it. You can’t edit it. You can’t pause it. If your hands are tired, the balls drop. If your mind is racing, they fly off course. There’s no filter. No algorithm. Just you, the balls, and the space between.

That’s why Hoe’s Odes has found an audience among therapists, meditators, and people who’ve lost something they can’t name. A yoga studio in Toronto started playing recordings of his juggling sounds during sessions. A podcast in Berlin interviewed him about ‘the silence between throws’. A university in Berlin even added a course called ‘Movement as Metaphor’ - using Quinine’s work as a case study.

He doesn’t have a website. No Instagram. No YouTube channel. If you want to see him, you have to be in the right place at the right time. Sometimes he’s near the Canadian Museum of History. Sometimes he’s outside the Winnipeg Art Gallery. Last month, someone spotted him near the frozen river, juggling snowballs. He didn’t catch any. They melted in his hands. He smiled.

What Comes Next?

Quinine is working on a new collection called ‘The Fourth Ball’. He won’t say what it’s about. Rumor is, it involves a glass orb, a single spotlight, and a recording of his father’s voice saying, ‘You always were too careful.’

He’s also started teaching. Not classes. Just sessions. One-on-one. He meets people in parks. He doesn’t teach them to juggle. He asks them to remember the last time they felt completely lost - and then, for five minutes, to move like they’re trying to catch something they can’t see. Most cry. Some laugh. A few never come back.

He doesn’t mind.

He says, ‘If you’re looking for answers, go find a book. If you’re looking for a moment - I’ll be the one with the balls.’

And if you ever find yourself in Dubai, wondering what to do after a long flight, you might stumble across a video call escort who knows how to hold still. Not because she’s waiting for you - but because she’s waiting for something else. Something that falls, and rises, and never quite lands the way you expect. That’s when you realize: maybe we’re all just trying to catch what we can’t name. esxort dubai might not be the answer, but sometimes, it’s the question you didn’t know you needed.

Where to Find His Work

You won’t find Hoe’s Odes on Amazon. It’s not published. Not yet. But if you know where to look, you can find copies in small bookstores in Winnipeg, Toronto, and Berlin. They’re printed on recycled paper, bound with twine, and stamped with a single red dot - the mark of a catch that worked.

There’s also a 12-minute film, shot in black and white, called ‘The Ballad of the Third Ball’. It’s on Vimeo, but only if you know the password: ‘quintessence’. He gave it to 12 people. Each one was asked to pass it on to someone who needed to see it. You can find the link if you ask the right librarian in the right city. Or you can just wait. He’ll be somewhere. Juggling. Waiting. For you to stop.

And if you ever need to remember what it feels like to believe in something you can’t hold - just look up. Watch the sky. Wait for a bird. Then look down. And try again.